The Making of Helen of Troy

The Making of Helen of Troy

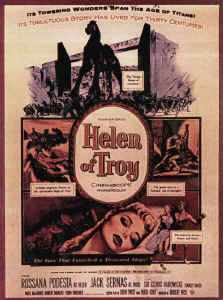

Helen Of Troy was one of the most popular and successful of the "Sword and Sandal" epics of the fifties. Directed by Robert Wise, and shot on a lavish scale in CinemaScope with the proverbial "cast of thousands", it was released by Warner Bros. in 1955. This is the story of that production.

The Director

The film career of Robert Wise had been as diverse as it was distinguished. Born on 10th September 1914 in Winchester, Indiana, Robert E. Wise was the youngest of three brothers. He first entered the film industry at the age of 19 when one of those elder brothers, who was working in the accounting department at RKO, got him a job in the studio's sound department. A head sound effects man, realizing the potential of young Wise, made him his protégé, and he worked on many films at the studio, until, tiring of editing sound effects and music, he began to edit film as well, notably; The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1939); My Favorite Wife(1940) and The Devil and Daniel Webster(1941) Also in 1941, Orson Welles, impressed with his body of work, asked Wise to cut his masterpiece; Citizen Kane, which earned him an Oscar nomination for Best Editor. After editing The Magnificent Ambersons(1942), he was given his first chance behind the camera, as co-director, on Val Lewton's The Curse of the Cat People(1944). He followed this with The Body Snatcher(1945), also for Lewton. For the next four years, Wise toiled in RKO's B-picture department, consolidating his reputation, until he was assigned to Blood on the Moon(1948), and turned in a first-rate, atmospheric western. He followed this with The Set-Up(1949), a prizefight drama that took place in "real time", and it was this film that proved to be the turning point in Wise's career. Moving on to other studios, he directed such films as; Two Flags West; The House on Telegraph Hill; the classic science fiction drama, The Day the Earth Stood Still; The Captive City, and Destination Gobi, for Warner Bros. and Twentieth Century-Fox, and then he moved to MGM in 1953 for Executive Suite. It was at this point in his career that wise was approached by Warner Bros again, and was asked to direct Helen of Troy, which would be his first feature in CinemaScope.

A challenge

|

| Wise directs Jack Sernas |

Wise was on holiday in San Francisco, after completing Executive Suite, when his agent informed him of Warner's offer. Intrigued by the idea and curious as to whether he could pull off an "epic" - a complete change of direction from his usual style, Wise agreed to do it . He had seen the CinemaScope process demonstrated at Fox a year or two prior to his involvement with Helen and he had realized that CinemaScope was seen as the sort of thing where you point the camera at the actors head-on, and do a ten-minute scene in one shot; no cuts; no angles; no over-the-shoulder stuff. Wise saw this as a challenge; feeling that there was no real reason why he couldn't shoot Helen of Troy in the same way he'd shot his black and white films, and to hell with the frame size! In fact, with the help of Harry Stradling, the cinematographer who would be assigned to the film, Wise was proved right, and Helen was probably one of the first 'Scope films to be shot that way.

Cinecitta

The vast Cinecitta Studios in Rome, built in 1937 on the orders of Mussolini to "rival the biggest and best of Hollywood"(after sending his son there to see what the studios looked like) was enjoying something of a revival when Wise and his crew of thirty Warner Studio technicians arrived in 1954. Business was booming, and several costume epics were in various stages of production. Paramount had gone there to shoot Ulysses with Kirk Douglas and Sylvana Mangana. Anthony Quinn had just completed Attila the Hun with Irene Pappas and a young Sophia Loren; and Howard Hawks was wading half-heartedly into Land of the Pharaohs, with Jack Hawkins and Joan Collins, after completing exteriors in Egypt. Wise was also slightly perturbed to find that a "home grown" Helen of Troy film had just been completed, starring Hedy Lamarr. Planned as a major production, this aborted spectacular emerged as a modest 73 minute film entitled LAmante di Paride (US title: The Face that Launched a Thousand Ships), that, thankfully for Warner Bros, came and went so fast that nobody really noticed.

Casting.

Casting the role of Helen - "The most beautiful woman in the world" - was no small problem for Wise. Most of the current Hollywood "love goddesses" had been considered, including Lana Turner; Elizabeth Taylor; Rhonda Fleming; Yvonne de Carlo; Ava Gardner, and - Warner's preferred choice - Virginia Mayo. Wise felt that using relative "unknowns" for the principle leads would be more effective, and he most definitely did not want Virginia Mayo under any circumstances!

|

| Rossana Podesta as Helen |

Eventually the part went to Rossana Podesta, an established star, who'd had a small part in Ulysses and had appeared in a number of mediocre and non too successful Italian films, but was the requisite "unknown" outside Italy. The one problem was that Podesta didn't speak any English at that time. Wise wanted to avoid a clash of accents or dialects amongst characters who were supposed to be speaking the same language, and the rest of his cast were largely British, classically trained actors, such as Cedric Hardwick; Stanley Baker; Harry Andrews and Niall MacGinnes for the male characters, and Janette Scott and Nora Swinburne for the females.

|

| The meeting in the fisherman's hut. Helen tells |

The only way around this was to have Podesta learn her lines by rote, and Wise employed a voice coach to help her, with remarkable effectiveness. Another member of the female cast had the same problem - and endured the same solution - the part of Helen's handmaiden had gone to newcomer Brigitte Bardot! French actor, Jacques (Jack) Sernas, had been cast as Paris, the son of Priam, king of Troy, and he could speak English. Unfortunately, although he had a fine speaking voice, the timbre didn't match the rest of the cast, and his voice was dubbed, as were the parts of other Italian speaking actors.

The Production

Wise ran into

problems almost from day one. There is no Producer credit on Helen

of Troy, so there was no one person responsible for getting the show

on the road. Wise, arriving in October of 1954 to carry out an initial

survey of facilities and locations, found that an English executive was

in charge of "European Production". This man was appointed "Administrator",

not "Producer", and it soon became apparent to Wise that he

was not going to be particularly helpful. Realizing the complications

of the huge production that he had taken on, Wise attempted to get a Producer

credit from the studios, but they refused. He also found that this "Administrator"

had appointed two Production Managers for the film; Maurizio Lodi-fe and

Giuseppi De Blasio, whom Wise found, thankfully, to be both amiable and

competent. But the obstructive attitude of the Administrator would continue

to be a millstone round Wise's neck from the time of his return to Italy

the following April to commence shooting, and for the subsequent ten months

of production.

Wise now had his complete crew, which was a pretty mixed bag, consisting

of his key Americans; some English and Italian, and also a few French.

|

| Stanley Baker, as Achilles, arrives to sort things |

On-set language

problems turned out to minimal, though, as Wise found out that there would

be at least one crew member on each team who could act as interpreter.

One thing that hadn't been realized though was the amount of time that

would be required to build the sets and stock them with props. All the

sets on Helen of Troy were built from scratch; there was to be

no re-using of existing ones. The walls of Troy were built from the same

type of stone and mortar that the ancients used. The Trojan palace, the

shops, houses and streets of Troy were designed and built as they originally

were, and then stocked with period furniture. And, in addition to the

laborious construction of ancient Troy, circa 1200 B.C.- the period of

Helen and Paris - several full-sized ships were built, to be manned by

dozens of rowers. Working replicas of Greek war machines were constructed,

along with the thousands of weapons that would be needed to re-create

the Siege of Troy: swords; shields; spears; bows and arrows, and hundreds

of sets of body armour and helmets. Even two pairs of authentic cesti

- mailed and studded boxing gloves, used by Greeks and Trojans in personal

combat - were made, such was the attention to detail.

|

| The Trojans are none to pleased to see what |

Visually, Helen of Troy is a far more ambitious production than most of its contempories. The spectacular "look" of the film is due to the combined efforts of the four men responsible for the various aspects of production and costume design. Maurice Zuberano's continuity sketches coupled with Edward Carrere's production design gave Helen its spectacular sets, and also enabled cinematographer, Harry Stradling, to overcome CinemaScope's depth of field problems which had concerned Wise from the start. An uncredited Ken Adam - later to design Dr Strangelove for Stanley Kubrick, and several of the famous James Bond sets - was brought in for his expertise on period ships. And finally, the beautiful and extremely accurate costumes were the work of Roger Furse, who would go on to create the impressive costumes for Cleopatra and Camelot.

It took roughly six months to build the big exterior sets, and these were the first that Edward Carrere started on as it was realized that they would take the most time to construct. Even then, Wise wasn't able to start shooting on them when he wanted to, but had to begin filming on some of the interior sets first, (with their real marble floors!) until the exterior sets were ready. In fact, the painters were still putting the finishing touches to the exterior set on the day that they actually began filming on it.

With the production

under way, Wise was able to concentrate on the main dialogue scenes, while

second unit directors Gus Agosti, and the inestimable Yakima Canutt, handled

minor scenes and the spectacular action sequences respectively. For the

action scenes, a crew of around eighteen stuntmen were recruited from

England, as the Italians, at that time, were not renowned for their proficiency.

The English crew would perform the key stunts, and would also train the

Italians to do the simpler stuff. In addition, a construction manager,

also from England, was brought over to supervise the construction work

involved. Apart from the usual sprains and bruises these sequences were

generally accident-free, although, sadly, an electrician lost his life

when he fell from a parallel (a platform for cameras or lighting rigs)

forty feet to the ground

|

| Harry Andrews as Hector unsuccessfully |

Great care was also taken to avoid injury to any of the animals in Helen, as the film industry had had a miserable reputation in the past for cruelty inflicted on unknowing animals used in filming, a notorious example being the deaths of over a hundred horses during the filming of MGM's 1925 version of Ben Hur. Another depressing example would be Warner's 1936 Errol Flynn vehicle, The Charge of the Light Brigade, where horses were driven over rocky ground in which pits and trenches had been blasted by dynamite to accommodate low angle filming. Many horses, tripped by wires, tumbled into these jagged holes and died horrendously. After members of the local SPCA visited the Sonora location, charges were filed against the studio. (Several years after Helen of Troy, another production, Solomon and Sheba, filmed by a different studio in Spain, would achieve similar notoriety by driving horses over a "cliff" for the climactic battle scene, with predictable results).

On a less somber note, one of the shots that would be required was the dragging of Hector's corpse behind the chariot of the victorious Achilles. This was considered too dangerous even for a stuntman, so the only alternative was to use a dummy. "These are the most miserable things to work with in films", said Wise. Nevertheless, special effects supervisor Louis Lichtenfield, began tests on various types of dummy, in an attempt to get some kind of realistic movement out of the "body", rather than have it bounce all over the place like the rubber man it essentially was. The end result was, well, adequate. And though it's only seen briefly, Wise still considers it to look fake, and thinks of it in much the same terms as the robot Gort's foam rubber suit in his earlier film, The Day the Earth Stood Still. Of course this brings to mind a certain giant shark in a much later film, proving that money and technology don't always deliver the goods.

And on the subject of props, no film about the siege of Troy would be complete without a wooden horse. Initially, there had been some concern as to how "This great damn thing", as Wise called it, could be made reasonably cheaply and still be able to be moved. Here's how a studio hand-out described its construction:

|

|

| The Trojans pretend to strain as they |

One of the biggest props ever built for a film |

"The tremendous beast consumed more than thirty full-grown trees in the building - fir, beech and poplar. More than a thousand pounds of nails and a wagon load of screws, wooden pegs and iron rings went in to the construction. The wheels for the platform were eight feet in diameter and two feet thick. The platform itself was sixty feet long. It had built-in benches and an air-conditioning system, otherwise the players who occupied its interiors might have suffered heat-stroke in the broiling Italian summer. Twenty five men occupied the horse's interior. The horse was forty feet high, and weighed, complete, more than eighty tons."

In actual

fact it was built mostly from balsa wood, and moved quite easily on its

wheels - so much so, in fact, that the extras who were dragging it into

the city had to be told to look as if they were struggling with it, as

it moved too easily. Hyperbole aside, though, it was the largest prop

ever built for a movie.

Another essential for a historical epic - and no less unpredictable -

are the extras! Not quite the 30,000 claimed in some of the publicity

hand-outs, but several thousand anxious-to-please Italians nonetheless.

Obviously the first problem with a huge number of people in a period piece

is getting them costumed and on set, so this chore would begin early.

Back then there were people that the studio could call who would each

bring in another twenty five prospective Greeks and Trojans from their

neighbourhood. They were known as "Capo gruppo", or group captains,

and they would be given a section number by the assistant directors, and

a map of where their section would be on the set. There would also be

a core of experienced, professional extras. These trained people would

be given proper costumes, and would be placed in the foreground of any

particular scene. The rest of them would be given what Wise describes

as "Half-ass" costumes, and were used in the crowd shots, where

they wouldn't be noticed. Occasionally, though, in their enthusiasm, they

would push themselves down past the properly made up and costumed extras

and appear right in front of the camera with askew wigs and modern shoes

instead of sandals. Wise found that many of the Italians showed a keenness

far above the call of duty, and recalled that Orson Welles had once remarked

that: "All Italians are actors - only the worst of them are on the

stage".

|

| A quick kiss before Paris takes |

Meanwhile, back at the ranch, the Administrator - or Mr. X as we'll call him, seemed to be doing his best to undermine Wise at every opportunity. As the huge production began to slip, not surprisingly, behind schedule, Mr. X began to criticize and complain about Wise's decisions. Not to Wise directly, but via a series of cables to Jack Warner and the executives back in Burbank. The result of this would be a telephone call to Wise in the middle of the night from Hollywood, with the studio wanting to know what was going wrong. Wise would then have to explain what he was doing and why - and would invariably receive the backing of the studio, in spite of some of the unforeseen expenditures that were being incurred. Nevertheless, Mr. X continued with his sinister activities, much to the outrage of the secretaries who had to send his nefarious cables for him. So incensed were they that they began to keep copies of them to show to Wise. He, in turn, sent all his cables via Mr. X's office so that he would know exactly what the director was doing,. This went on all through the last half of the production, and no director needs that kind of pressure. Wise found it extremely wearing, but, as he says, "We got through it."

Disaster

With most of the big Troy scenes shot, the main unit moved to a small town on the sea shore for some location work. One evening, when the shooting there had been completed - ahead of schedule - several of the key crew members had gone up to cinematographer Harry Stradling's hotel room, for drinks on the terrace overlooking the ocean. You can probably picture a very convivial scene as they relax, no doubt feeling quite pleased with themselves to be back on course after a difficult and sometimes complex shoot. Then the telephone rang. Edward de Blasio took the call, and sat listening, the colour draining from his face. The room suddenly went quiet. "That was the studio," he said. "The set's just burned down."

They all piled into cars and headed back to Rome, but on the way, they managed to persuade themselves that perhaps this was just a case of the usual Italian overstatement; sure, there was a fire, and maybe a little damage, but nothing too serious. Panic receded, and so they made a detour back to the coast to check out the boat they would be using for some scenes in a couple of weeks. But once at the seashore, they met some of the crew who had been at the studio in Rome the day before, when the fire had started. The second unit had been shooting some scenes of the Battle of Piraeus, and had broken for lunch, leaving some Italian firemen to keep an eye on the burning siege towers. Apparently everything looked quiet so they decided to have some lunch as well. They were happily enjoying their meal when somebody looked up and saw that the fires were spreading everywhere! Someone described the firemen as being like the Keystone Cops; pulling out hoses that were full of holes and leaking all over the place, and a couple of firemen grabbing opposite ends of the same hose and running towards the flames with it. It would be funny if it wasn't so serious- to the tune of the half million dollars that went up in smoke with the set.

The major problem was that the sacking of Troy had yet to be filmed, and there wasn't much of it left. Maurice Zuberano proved to be godsend; making revised sketches, rearranging moveable fronts that had survived the blaze, and masking off damaged areas. The ingenuity of Wise and his crew paid off, and it is to their credit that, watching these scenes in the completed film, you would never know how close they had come to losing the film.

Epilogue

|

| The end of Troy |

Released in 1956, Helen of Troy was a hit for Warners. And while the script and some of the performances may not compare favourably with, say, Robert Rossen's Alexander the Great, the visuals easily surpass most of its contempories. Every dollar is up there on the screen. Would Wise do it any differently today? With hindsight, he says he would probably have taken more time in preparation and used bigger names in the lead roles of Helen and Paris. but generally he is satisfied with the film. It did his career no harm at all and he still occasionally receives letters from people who've seen it and loved it! He would go on to direct such classics as West Side Story, The Sound of Music , The Sand Pebbles, and, of course, many others-but never another "epic". "They're just not my cup of tea," he says.

Anyone who would like to dig deeper into some of the topics and films that we have mentioned might like to go to some of the sources that I have used when researching the articles in these pages. So here are several books that I can recommend. I consider each of them to be an invaluable source of information in their respective fields. They are all clearly written and hugely entertaining (to a movie maniac, that is).

The History of Movie Photography by Brian Coe, (Ash & Grant 1981)

Wide Screen Cinema & Stereophonic Sound by Michael Z. Wysotsky, (Hastings House/Focal Press Ltd. 1971)

Widescreen Cinema by John Belton,( Harvard University Press 1992)

The Ancient World In The Cinema by Jon Solomon [revised and expanded edition] (Yale University Press 2001)

Spectacular! The Story Of Epic Films by John Cary Edited by John Kobal, (Hamlyn 1974)

You may find some of the older publications are out of print now, but they are absolutely worth tracking down. I will, of course, continue to update this list as we go along. Enjoy.

J.H.